Research Roundup: Sample Collection for COVID: How Does Saliva Stack up Against Swabbing?

December 15, 2021

Welcome to Research Roundup! Each month COPAN will feature a comprehensive review and commentary on recent scientific publications covering a particular topic of interest. COPAN’s Research Roundup is authored by Dr. Susan Sharp, COPAN’s Scientific Director!

In this month’s edition, Dr. Sharp reviews how saliva samples compare against swab samples for reliable downstream molecular testing of COVID-19.

Scientific Review of Publications

Specimen Collection in Scientific Literature

There have been many articles in the scientific literature over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic regarding specimen collection, and there will certainly be more to come. Initially these studies were focused on the best collection possible using the nasopharyngeal (NP) swab, which comes as no surprise given its status as the gold standard for respiratory tract specimen collections to detect viral infections.

However, with the never before seen, unprecedented, demand for NP swabs during the pandemic there was a shortage in availability of NP swabs, which resulted in the evaluation of other specimen types. Early studies focused on throat and nares swabs, comparing them to NP swab collections for the accurate detection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in clinical specimens. But it was soon realized that even these ‘routine’ swabs eventually were in short supply. Evaluations then turned to using saliva specimens, gargle washings, etc., as alternative sources for SARS-CoV-2 specimens. Some, but not all, saliva evaluations included a comparison to the gold standard NP swab.

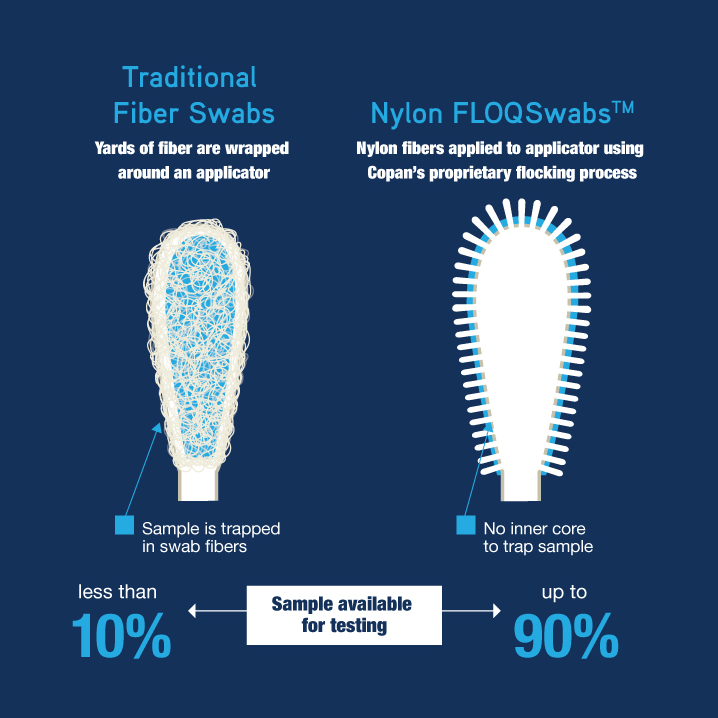

Introduced more than a decade ago by COPAN, flocked NP swabs have been widely adopted and endorsed by scientists as a superior swab, absorbing and releasing more clinical sample than previous swab materials and designs. It is important to note that in the following literature review not all study teams described the specific swab material they used for the NP swab collection. In many cases it was a flocked NP swab but in others it could have been flocked, polyester fiber wrapped swab, foam tip swab or something else.

Section I: Studies Comparing Specimen Types

NP Swabs vs Saliva: A Meta-Analysis

A review of recent literature comparing NP swabs to saliva for the molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 includes a meta-analysis of 16 studies. This analysis determined that saliva had a pooled sensitivity was 83.2% and the pooled specificity was 99.2%, and that the NP swab had a sensitivity of 84.8% and a specificity of 98.9% showing comparable detection, especially in the ambulatory setting. This study emphasized that there was significant variability in patient selection, study design, and stage of illness at which patients were enrolled in each of these studies.

NP Swabs vs Saliva in Transport Media

In other studies, Berenger et. al., showed that when obtaining specimens in known positive patients in order to compare saliva collected in a viral transport medium such as UTM®: Universal Transport Medium™ and NP swabs in viral transport media, and considering a positive result in either specimen as a true positive, that saliva had an agreement of 84.1% as compared to NP swab which had an agreement of 91.3%.

The study by Kandal et. al., also using an adjusted sensitivity where any positive specimen was considered a true positive, demonstrated a sensitivity of 91% for saliva and 93% for NP swab samples in an outpatient setting.

Supervised NP Swabs vs Self-Collected Saliva

Kojima et. al., showed that clinician-supervised oral fluid swab specimens detected 26 (90%) of 29 infected individuals, that clinician-supervised nasal swab specimens detected 23 (85%) of 27, clinician-collected posterior nasopharyngeal swab specimens detected 23 (79%) of 29, and unsupervised self-collected oral fluid swab specimens detected 19 (66%) of 29. There was no difference in testing performance when comparing those patients with and without active symptoms. They concluded that ‘supervised’ self-collected oral fluid performed similarly to clinician-collected nasopharyngeal swab specimens.

Fan et. al., demonstrated that both saliva and NP swab specimens performed well, with 97% agreement and concluded that saliva can be considered a suitable alternative for noninvasive but ‘well-instructed’ self-collection.

Comparing Saliva, Nares, Midturbinate, and NP Swab Collection

Chu et. al., when testing outpatients for COVID-19, found that 28% of 107 participants tested positive using saliva swabs, 29% with midturbinate (midT) swabs, and 37% with NP swabs showing that NP swab collection has the highest sensitivity followed by midT then saliva.

Similarly, Boerger et. al., showed that as compared to NP swabs, saliva exhibited a sensitivity of 90.9%, while patient-collected midT swabs exhibited a sensitivity of 93.9%.

Hanson et. al., showed that in patients suspected of having COVID-19, nares swabs and saliva collections had a positive % agreement of 86.3% and 93.8% respectively, as compared to health care worker collected NP swabs.

Fernandez-Gonzalez et. al., likewise showed that saliva collected under the supervision of a health care worker in a community setting had a sensitivity of 86% as compared to NP swab collections.

In addition, Pasomsub et. al., showed that the sensitivity of the saliva samples were 84.2% as compared to NP swabs and conclude that saliva might be an alternative specimen to collect for COVID-19 as it is non-invasive and non-aerosol generating.

Comparing Saliva and NP Swab Collection in Pediatric Populations

Studying a solely pediatric population, Banerjee et. al., found that the overall agreement between the performance of saliva and NP swabs of 94.5% and that the sensitivity of saliva as compared to NP swabs was 93%. In a pediatric population they conclude that saliva is a reliable and easy specimen which negates the need for direct interaction with a health care worker. Saliva collection in children provides a good option for pediatricians that are hesitant to collect NP swabs in private practice setting. The study noted that widespread implementation of saliva sampling could be extremely helpful for mass screening of asymptomatic children in schools.

Section II: Studies on the Timing of Collections

Several studies have shown that the timing of specimen collections is also very important in the accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Alkhateeb et. al., found that as compared to NP swabs, saliva demonstrated higher sensitivity in symptomatic patients (80%) vs. asymptomatic individuals (36%).

Lafer et. al., showed that viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 were highest in the first week of disease in mouthwash, buccal swab and nasopharyngeal swab collections.

Kerneis et. al. found that saliva shows significantly lower cycle threshold (CT) values in symptomatic participants tested ≤ 4 days after symptom onset as compared to those tested after 4 days and those with no symptoms.

Likewise, Uddin et. al., showed that the sensitivity of the saliva specimens was 80.3% as compared to NP swabs, and that detection was higher in saliva (85.1%) among the patients who visited the clinic 1 to 5 days after of symptom onset. This suggests that saliva can be used accurately for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 early after symptom onset in both clinical and community settings.

Williams et. al., showed that in NP swab positive patients, 86% were also positive in saliva and that overall, the median CT value was significantly lower in NP swabs than saliva suggestive of higher viral loads in NPS. They were also able to show that in both samples there was a correlation between CT value and days from symptoms onset.

In a very recent publication, Defeche et. al., tied both specimen type and collection time together. In studying collections including NP swabs, OP swabs, Oracol-collected saliva, throat washes and rectal specimens, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire to correlate specific clinical symptoms with various sample specimens. Sampling was repeated after 7 to 10 days (T2), then again after 14 to 20 days (T3). At the first collection time (T1) the highest percentages of SARS-CoV-2-positive samples were observed for nasopharyngeal samples (84.3%), while 74%, 68.2%, 58.8% and 3.5% of throat washing, saliva, OP and rectal specimens tested positive, respectively. The sensitivity of all sampling methods except throat wash specimens decreased rapidly at the 2 later time points compared to T1. The throat washing method exhibited better performance than the NP swab at T2 and T3. They found that SARS-CoV-2 persists longer in the throat and saliva than in the nasopharynx and were able to conclude that NP swabs were the most sensitive specimens for early detection after symptom onset and that throat washing is a sensitive alternative method.

The Roundup: In Summary

Several different collection types have been found to work well if taken within a few days of symptoms and that NP swab collections are more sensitive when taken earlier in the infective process with COVID-19. Although most collections will give acceptable results in most assay platforms from symptomatic patients (> 80% sensitivity), overall, NP collections perform best.

The screening of asymptomatic individuals is usually performed using less invasively collected specimens such as nasal swabs or saliva, but these specimens will show lower viral loads and may be falsely negative especially if tested early in the disease process. However, these are the primary types of collections used when screening for work, school attendance, travel, etc.

Alternative collection techniques, like saliva, are inexpensive and can eliminate barriers to testing, particularly in underserved populations.

What are Your Thoughts?

Please fill out our brief 2-3 minute sample collection survey below to help COPAN better understand your laboratory’s needs! This information helps us develop innovative technologies so we can better serve our healthcare partners like you!

Stay Informed

With tens of thousands of scientific papers published each year, it is hard to stay informed on the relevant research. Each month COPAN’s Research Roundup will feature a comprehensive review and commentary on recent scientific publications covering a particular topic by experts in the field to help keep you up to date on the latest research. Sign up today so you don’t miss the latest findings!

About Dr. Susan Sharp

Dr. Sharp has been a clinical microbiologist and active member of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) for 30 years serving on various boards and committees. She is a Diplomat of the American Board of Medical Microbiology (ABMM) and a Fellow in the American Academy of Microbiology. Dr. Sharp served as the Chair of the ASM Public and Scientific Affairs Board’s Committee on Laboratory Practices from 2007 to 2015, as well as Chair of the Examination Development committee and Vice-Chair of the ABMM during 1999-2015.

Dr. Sharp has recently served as an Advisor to the CLSI Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Sub-Committee and she is a current member of the CLSI AST Resistance Working Group as well as the Methods Application and Interpretation Working Group. She is also an active member of the Board of Scientific Councilors for the Office of Infectious Diseases of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sharp is a Past-President of ASM and a former member of ASM’s Board of Directors. Dr. Sharp has given numerous lectures, seminars and workshops locally, nationally and internationally, and has numerous publications in the field of clinical microbiology. Her most prominent area of interest has centered on cost-effective, clinically-relevant diagnostic microbiology.